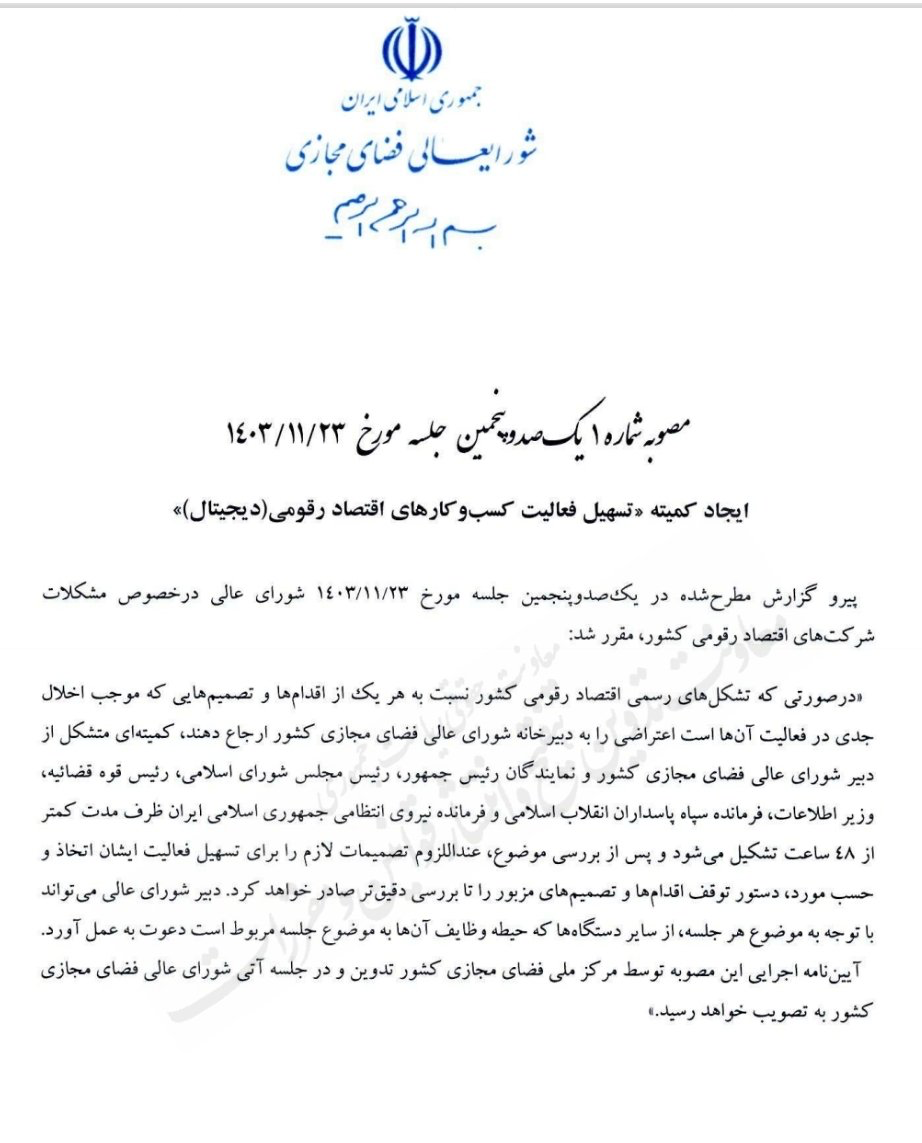

In recent months, with the adoption of a plan known as Internet for Social Strata by the SCC, one of the most troubling schemes of targeted censorship in the Islamic Republic of Iran entered an official phase. Although the resolution had been passed in February 2025, its implementing bylaw was delayed until after the recent Iran-Israel war in June 2025. On the very day when the state spokesperson was speaking to reporters about the prospect of a “freer internet,” the SCC, chaired by the president, approved the bylaw establishing the Committee for the “Facilitation of Digital Economy Businesses.”

This plan, also referred to as the Tiered Internet, is a model of controlled and discriminatory access that not only violates the principle of equality in access to information but also signals the maturation of an authoritarian digital project in Iran.

In the Tiered Internet system, users are classified into different levels of access to the global internet based on characteristics such as profession, education, institutional affiliation, or even political orientation. This classification, implemented through technical infrastructures such as the SHAHKAR system, the national firewall, and IP whitelists, allows the regime to exempt certain individuals from nationwide censorship restrictions.

According to available documents and reports, roughly 50,000 people in Iran currently enjoy access to an internet with fewer restrictions or no filtering at all. This privileged group includes government officials, regime-affiliated journalists, university professors, clerics, and other figures close to the establishment.

The operational model of the Tiered Internet rests on three pillars:

- Special SIM cards and VPNs: government-issued SIM cards and state-approved VPNs that are activated only for designated groups.

- IP whitelists: exempting specific users or institutions’ IP addresses from the national firewall.

- Access through designated institutions: such as universities, news agencies, or government-affiliated offices that provide unrestricted internet to their staff or members.

This infrastructure had previously existed in a limited form but is now being expanded in a structured and deliberate way. In this framework, access to the open internet is no longer a technical privilege but a marker of participation in a discriminatory system. Those placed on the whitelist and enjoying unfiltered access either remain silent or treat it as a natural entitlement, when in reality, it is evidence of collaboration with a project that deliberately denies millions of other users their equal right to access.

In contrast, some of these privileged users have chosen transparency over secrecy, by exposing special access arrangements or even sharing their freer internet connections with others. This is where digital resistance tools come into play. Services like Citylink or projects such as NasNet Connect enable a reverse use of the censorship system. In these methods:

- A user with privileged access (for example, through a special SIM card or university network) sets up an intermediary server.

- Other users connect to this server through the domestic internet and, from there, gain access to the global internet.

This model is independent of the source of the internet: it could be Starlink, research center networks, or even tiered-access connections. What matters is the willingness to share and resist monopoly. In situations where the Islamic Republic cuts off international internet access in a province or region in response to protests or social crises, such methods become crucial instruments of digital resistance.

Conclusion

The Tiered Internet is not a rumor but a bitter reality of digital policymaking in the Islamic Republic. It is a project built on discrimination, justified with labels such as “child protection” or “supporting businesses,” yet in practice serving as an instrument of control, inequality, and repression.

Against such a structure, exposure and sharing can become effective steps in resistance. If you have “freer” internet access, break its monopoly. If you are on the whitelist, document and disclose it. It is silence that entrenches the architecture of digital discrimination, and it is the voice of exposure that marks the first step in breaking it.