This report examines the Islamic Republic of Iran’s overarching policies on surveillance and spying into the private lives of its citizens and reveals classified objectives embedded within the development of the National Information Network (NIN). Central to this effort is the so-called Oversight System in Cyberspace, a project of the Ministry of ICT designed to consolidate state control over the country’s digital environment.

In the Islamic Republic’s digital governance architecture, surveillance and interception play a central role. Many of the NIN’s core functions were explicitly designed to enable monitoring and interception. Technical evidence shows that the country’s lawful intercept systems diverge significantly from international standards meant to safeguard privacy and due process.

With its extensive coverage, large number of unique users, and centralized nationwide deployment, the NIN stands as one of the largest and most sophisticated surveillance and spying infrastructures under an authoritarian government anywhere in the world. Unique features, including systems such as SIAM, SHAHKAR, and HAMTA, are deployed for digital repression, with indications that Tehran has also sought to export these technologies to other authoritarian-leaning states.

The Islamic Republic is developing a wide range of surveillance and interception capabilities through modern technologies. CCTV cameras, facial recognition systems, mobile applications designed to capture the content of users’ private messages, and lifestyle assessment platforms all provide security agencies with powerful tools for extensive monitoring of Iranian citizens.

At the core of this surveillance architecture lies the National Information Network (NIN), often referred to in public discourse as the “National Internet.” Among its functions to restrict and control users, the NIN is best known to Iranian civil society for filtering and blocking online services. Although officially presented as a project to ensure independence of domestic connectivity from the internet, its primary function has been censorship and repression of the free flow of information. Yet beyond censorship, the system has also been designed to enable pervasive spying on citizens’ private lives under the rubric of “intelligence oversight.”

Violations of freedom of expression through filtering and censorship, as well as restrictions on the free flow of information via disruption or nationwide and local shutdowns, are the most visible human rights concerns tied to the NIN. What is less known, but arguably more alarming, is the development of multi-layered surveillance and interception capabilities within the NIN’s technical infrastructure. These systems serve distinct purposes: some are designed for mass surveillance, while others enable targeted tracking and espionage against specific individuals. The following sections examine these mechanisms in detail.

The Place of Surveillance and Interception in Iran’s Internet Governance

The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution (SCCR), the regime’s cultural policy body under the direct control of the Supreme Leader, adopted the “Regulations and Rules for Computer Information Networks” in 2001. This legislation laid one of the earliest foundations of internet governance in Iran. It required internet providers to deliver user activity data to the Ministry of ICT, which, upon judicial approval, would then be transferred to the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS). This regulation created a crucial legal basis for the Islamic Republic’s lawful intercept system, also referred to as intelligence oversight. From a technical standpoint, however, the system diverges significantly from global privacy and due process standards.

Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader, also established and controls the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC), which serves as the principal policymaker on internet affairs. One of its key resolutions, the “Obligations of the NIN” outlines six core domains of the NIN: communications infrastructure, independence, management, services, security, and economic model. Within this framework, the resolution mandates that the NIN must have “defined boundaries within which it is possible to monitor, oversee, and enforce all forms of state policies across every layer of the network.” Similarly, it makes surveillance “a requirement to guarantee the efficiency of other network services.”

The security domain forms the backbone of this resolution, though many of its provisions remain classified. Phrases such as “the ability to monitor, oversee, and enforce state policies,” “a unified and trusted identity management system,” and “comprehensive content filtering” reveal a strategic plan to expand tools that empower security agencies including the IRGC-IO to conduct surveillance and interception of citizens’ digital activities.

General terms such as “providing intelligence oversight and monitoring” appear only sparsely in later high-level policy documents. For instance, the Master Plan and Architecture of the NIN mentions two broad objectives related to intelligence oversight, while the Islamic Republic’s Strategic Document on Cyberspace defines one of its overarching goals as “achieving comprehensive and real-time oversight of domestic and international cyberspace developments.”

SIAM (Integrated Subscriber Information System) stands out as one of the Islamic Republic’s central tools of surveillance, interception, and even digital repression of citizens, illustrating the regime’s grip over Iranians’ digital lives. The system operates under the supervision of the Communications Regulatory Authority (CRA), an entity subordinate to the Ministry of ICT that also issues operating licenses for telecom providers. Information about one version of this system (dating to 2018) was leaked in 2022.

According to SIAM’s leaked API specifications, the system includes forty distinct functions for interception, surveillance, monitoring, tracking, and suppression of citizens. Among its most critical features is the ability to pinpoint users’ precise geolocation through their SIM cards. It logs all user call records, with real-time access available to oversight and security agencies.

SIAM also has the ability to throttle users’ internet speed or completely cut off their access. Furthermore, it can downgrade connections from more secure 3G and LTE networks to GPRS technology, which allows broader interception and monitoring. Data stored on this platform includes call records, messages, and even the content of users’ online communications (as shown in the leaked document, section Data), underscoring the depth of privacy violations. User data is ultimately transferred to centrally managed domestic cloud systems.

The use of mobile network infrastructure for targeted tracking is not new. Evidence of related research and experimentation had already surfaced in domestic law enforcement reports, and traces of such capabilities also appeared in recent cyberattacks on government servers. For example, a leaked letter from the head of the Parliament’s Security Directorate to Speaker M. B. Ghalibaf revealed that one of the measures taken after the outbreak of the 2022 protests was “collecting the phone numbers of MPs and parliamentary staff for security and intelligence agencies in order to monitor their possible presence in demonstrations.” This document shows that real-time location tracking of parliamentarians was operational, given that the protests were fluid in nature, emerging spontaneously at unpredictable times and in places not pre-determined, but rather through the gathering of initial protest groups.

Implementation of a Unified Citizen Identity Verification System

Identity verification is a core component of any security framework for access to network resources and services. Yet it becomes a potential tool of surveillance and interception when all services are routed through centralized, government-controlled gateways, comprehensive and mandatory Single Sign-On (SSO) systems.

In many countries, the use of authentication platforms by public service providers to manage and facilitate digital services brings significant benefits such as greater transparency, reduced fraud, and streamlined digital processes. In the Islamic Republic, however, where civil liberties are under constant pressure, these systems raise serious concerns. They can easily serve as powerful tools for tracking and compiling extensive records of users’ online and offline activities.

Although officially promoted as a mechanism to build trust in cyberspace, in practice such systems can be deployed to identify political opponents, restrict freedom of expression, and impose social control. An additional concern is that the integration of these platforms with technologies such as machine learning for behavioral analysis could escalate violations of privacy to a new level in the Islamic Republic.

In September 2019, the SCC adopted a resolution establishing the Reliable Digital Identity Framework. Its stated aim was to “create the necessary infrastructure for secure and reliable interactions in cyberspace.” The resolution requires that all technical, economic, cultural, social, political, and administrative interactions be conducted using authenticated identifiers.

According to the resolution, all entities operating within the NIN and its related platforms must have verified identities, and service providers are prohibited from processing interactions lacking valid credentials. The resolution specifies that all user interactions with the NIN or domestic platforms such as the “Smart Government Portal” must pass through an identity verification channel. This identifier is unique to “each individual,” and “every interaction” within the NIN must be traceable to a single, identifiable “person” (not user). The resolution mandates the Ministry of ICT to develop the infrastructure for this identifier, while other executive agencies, under the supervision of the National Cyberspace Center, are required to integrate the system into their application-layer services.

The resolution also introduced a three-year transition period for developing a “single gateway” for identity providers. Despite the passage of this deadline, the Reliable Digital Identity Framework has not been fully implemented. Once completed, it will provide the Islamic Republic with a comprehensive infrastructure to manage Iranian user identities across the internet. While officially presented as a framework to “guarantee complete identification of users and their interactions in cyberspace,” in practice it serves to facilitate tracking, content control, and the consolidation of state authority over digital governance.

In January 2024, the Supreme Commission for Regulation, part of the SCC and the highest regulatory authority in Iran, adopted the Executive Bylaw on Improving the Protection of Users’ Privacy and the Collection, Processing, and Storage of User Data on Online Platforms. This bylaw requires all domestic internet services to notify users of both mandatory and optional data access permissions, encrypt user data, and provide an option for “account deletion.” However, the bylaw states:

“In the event of a user request for deletion of related data, including account deletion … this must be executed immediately. Deleted data shall then be stored in a backup system, located offline and separated from the network, in order to comply with legal requirements, including Articles 667 to 670 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The data will be permanently destroyed only after the expiration of the legal or judicial deadlines.”

In other words, when a user requests to delete their account from domestic platforms, the account is not actually erased. Instead, the data is transferred to offline servers for retention.

Under the Code of Criminal Procedure (formerly the Computer Crimes Law), traffic data and user information must be retained for at least six months. This includes details such as “origin, route, date, time, duration, and volume of communications, as well as the type of services used.” It also covers “all information related to the user of access services, including the type of service, technical facilities employed and their duration, identity, geographical or postal address, internet contract (IP), telephone number, and other personal details.”

The resolution requires platforms to align their systems with the identity verification mechanisms to be developed by the National Organization for Civil Registration under the so-called Reliable Identity Ecosystem. In practice, this means that all internet service providers must rely on a single state-controlled system that checks user identities against the national civil registry (Ministry of Interior). The official justification is to “minimize the collection of identity data by platforms and service providers.”

Monitoring Citizens’ Lifestyles

The 7th 5-year Development Plan of the Islamic Republic, adopted in 2024 as the country’s five-year roadmap, places special emphasis on expanding digital infrastructure, e-government, and the digitalization of public services in the years ahead. A key element of the plan is the acceleration of nationwide identity verification systems. Given the absence of transparent laws, independent oversight, and respect for civil rights in the Islamic Republic, there is a high risk that such systems will become tools of privacy violations and social control. For now, many of these mechanisms remain in the design phase.

The most prominent initiative that captured public attention during the plan’s adoption was the Lifestyle Monitoring and Assessment System. Its purpose is to collect and analyze data on citizens’ behaviors, preferences, and everyday patterns. Responsibility for implementing the project has been assigned to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance in cooperation with the Statistical Center of Iran, with full deployment scheduled for 2025. In the initial draft of the plan, the project was titled “System for Monitoring, Evaluating, and Continuously Measuring Indicators of Public Culture, Religiosity, Spirituality, Morality, and Lifestyles,” but in the version submitted to parliament it was shortened to “System for Monitoring, Evaluating, and Continuously Measuring Indicators of Public Culture and Lifestyles.”

Under the 7th Development Plan, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance is obligated to establish a system for “monitoring, evaluating, and continuously measuring indicators of public culture and lifestyles.” Designed with an “Islamic-Iranian” approach, the platform seeks to track societal values, orientations, behaviors, and cultural-social institutions across Iran. All government agencies and database holders are required to supply continuous and comprehensive data to this system in real time. Although the operational details remain unclear, it is expected to aggregate data from diverse sources-including online purchases, use of digital services, consumption patterns, cultural and social activities, and even dietary preferences. Consolidating this information into a centralized database will allow authorities to conduct comprehensive and granular analysis of citizens’ lifestyles.

Deviation of Lawful Intercept Systems from International Standards

According to leaked documents from 2023, the Shamsa storage system has been used as the platform for retaining data collected through Iran’s lawful intercept infrastructure. The system described deviates significantly from the lawful intercept standards developed by 3GPP working groups and ETSI committees. These international standards define procedures and interfaces for exchanging legal warrants, enabling the interception of communications, and delivering content to authorized judicial authorities.

In contrast, the Islamic Republic’s lawful intercept framework complies with none of these safeguards. Analysis of leaked technical documents, cross-checked against enacted legislation, shows that the system lacks legal guarantees, fails to ensure the complete delivery of user information during activation, and is deeply embedded in mobile business systems to allow recovery of user content and manipulation of service access.

Oversight System in Cyberspace

One of the most consequential resolutions shaping the structure and future trajectory of the NIN and the Islamic Republic’s model of internet governance is the Master Plan and Architecture of the NIN, adopted by the SCC in 2020. This resolution serves as a roadmap for developing the internet in Iran, setting out the general framework, objectives, and technical, legal, and executive requirements for managing the NIN. Within this plan, thirty objectives are listed for the network. Notably, the 28th objective is marked as “classified and not for publication.”

Following a cyberattack on the email servers of the Deputy Prosecutor General’s Office for Cyberspace, previously unseen details emerged about the operational mechanisms and expansion plans of Iran’s censorship and filtering system. The leaked documents revealed the activities of the Committee to Determine Instances of Criminal Content, commonly known as the Filtering Committee, the principal body responsible for internet censorship and service blocking in Iran. The committee is composed of twelve other institutions and operates under the authority of the Deputy Prosecutor General’s Office for Cyberspace.

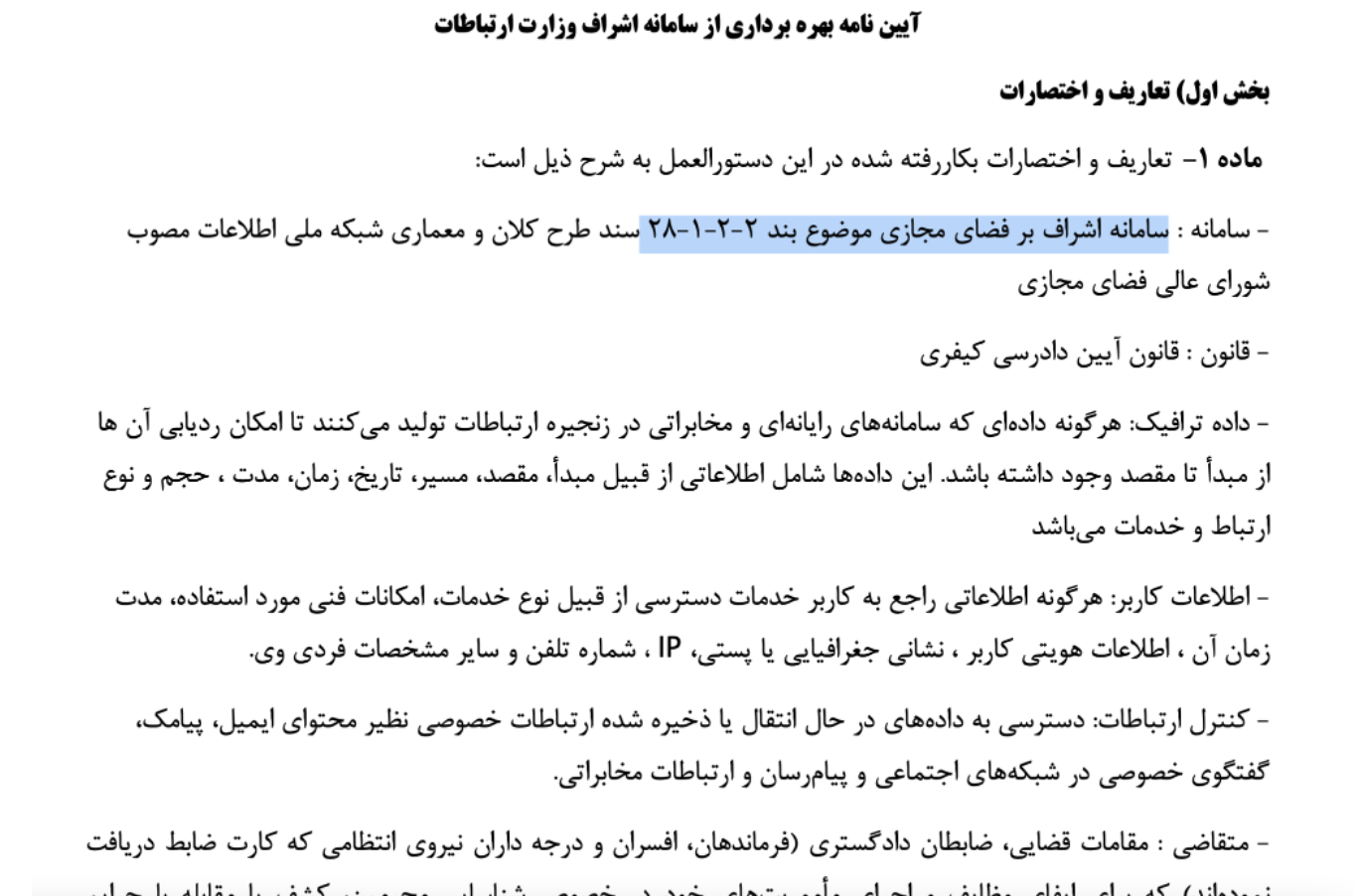

Among the documents was a draft regulation titled Bylaw on the Operation of the Oversight System of the Ministry of ICT. This file had been sent by the Filtering Committee to the SCC. The draft explicitly states that the “Oversight System in Cyberspace, as defined in Section 28 of the Master Plan and Architecture of the NIN,” is the same 28th objective that, two years earlier, had been labeled “classified and not for publication” in the officially released plan.

The draft bylaw states that all forms of “traffic data, such as origin, destination, and date” of communications, as well as “user information,” must be stored and, in cases where there is “strong suspicion of a crime,” may be provided to an “applicant” upon receiving judicial authorization.

According to these documents, the expected functions of the Oversight System in Cyberspace align with the Islamic Republic’s lawful intercept framework, which, as shown in earlier research, deviates significantly from international standards. This is the first time a formal document has surfaced that explicitly describes part of Iran’s lawful intercept operations under the title of the Oversight System.

Although the Oversight System’s main objectives are absent from the published resolution of the NIN, the bylaw itself discloses important details about the scope of such “intelligence oversight;” for instance, defines the range of eligible applicants as:

“Judicial authorities; law enforcement officers (commanders, officers, and ranking personnel of the police holding official credentials); … agents of the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS) and personnel of the IRGC-IO …”

The draft further references the IRGC statute concerning “actions against the Islamic Republic,” a classification of security offenses. This highlights the significance of the Oversight System within the regime’s broader security apparatus. Most notably, however, the Ministry of ICT is given access to all data exchanged nationwide. The draft specifies:

“For case-specific inquiries regarding traffic data or user information, the applicant shall submit a request, detailing relevant evidence and basic identifiers such as source or destination IP, date, time, type of service, and destination site, through the system to the judicial authority handling the case. Upon judicial approval, the requested data will be automatically delivered through the system in execution of Article 670 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.”

No further technical details on the Oversight System, or its integration into the NIN, are publicly available. However, previous evidence from platforms such as SIAM, HAMTA, and SHAHKAR demonstrates that the Ministry of ICT is actively developing infrastructure that enables full-scale interception of citizens’ traffic data and comprehensive surveillance, in line with regulations first enacted by the SCCR more than two decades ago.

Conclusion

An examination of the Oversight System in Cyberspace shows that it is one of the most complex and expansive surveillance projects developed by the Islamic Republic, designed to control, monitor, and intercept citizens’ digital communications. Evidence found in laws and official resolutions, particularly the NIN architecture plan and its implementing bylaws, demonstrates that the system constitutes a central element of the regime’s broader strategy to manage cyberspace and suppress the free flow of information.

The implementation of such a system carries profound consequences for civil liberties and human rights. Continuous monitoring of digital communications represents a clear violation of privacy and provides an effective tool for silencing political dissent, restricting the activities of civil society, and enforcing social control. Beyond undermining digital security, the system fosters self-censorship, erodes public trust in the online environment, and limits the free exchange of information.

From a technical perspective, the Oversight System and similar surveillance platforms in Iran show significant deviation from international standards on privacy protection and digital security. Unlike lawful intercept frameworks in democratic states, implemented under judicial oversight and within transparent legal boundaries, the Islamic Republic’s surveillance systems lack transparency and independent regulation. Furthermore, the emphasis on mandatory identity verification and centralized data aggregation raises state control over the internet to unprecedented levels.

Ultimately, the leaks and disclosures surrounding the Oversight System highlight the urgent need for greater awareness and demands for transparency in Iran’s digital governance policies. Civil society, media, and human rights organizations must respond with documentation, technical analysis, and international pressure. Without accountability and independent oversight, the deployment of such systems will only deepen digital repression, facilitate human rights abuses, and entrench comprehensive state control over Iran’s internet.