This report provides a comprehensive evaluation of the claims related to the installation of cameras and microphones in the electric taxis of "One Trip," a service operating with investment from Babak Zanjani. The present analysis has three main pillars: the legal framework for privacy in Iran, an assessment of the safety justifications for in-vehicle surveillance, and a comparison with international practices.

In the days when Iranian public opinion was shaken by the murder of Elaheh Hosseinnejad, the economically corrupt figure Babak Zanjani made headlines by announcing the launch of the "Dot One" taxi service; a service intended to cover the "inside of the cabin" with cameras, live monitoring, and "event recording." At the same time, a rumor circulated that "microphones" would also be installed in these taxis.

Finally, in the last week of August 2025, 250 of "Babak Zanjani's electric taxis" entered Tehran's urban transportation fleet. Meanwhile, media field investigations show that there are specific references to cameras and monitoring, but as of the time of this report, no reliable public document has been found regarding the recording of "audio" in this fleet. In his interviews about this project, Zanjani has spoken of installing cameras, monitoring from a "superior headquarters," and event recording, without any mention of microphones.

Social Tragedy, Marketing Context

Elaheh Hosseinnejad, a 24-year-old woman from Tehran, was murdered after getting into a passing car; a case that led to the arrest of the accused, the formation of a public trial, and the issuance of a verdict, sparking a wave of demand for safety standards in urban travel, from ride-hailing apps to private passenger transport. in such an atmosphere, any plan that presents "in-cabin surveillance" as a safety response inevitably comes under the scrutiny of public opinion and legal experts.

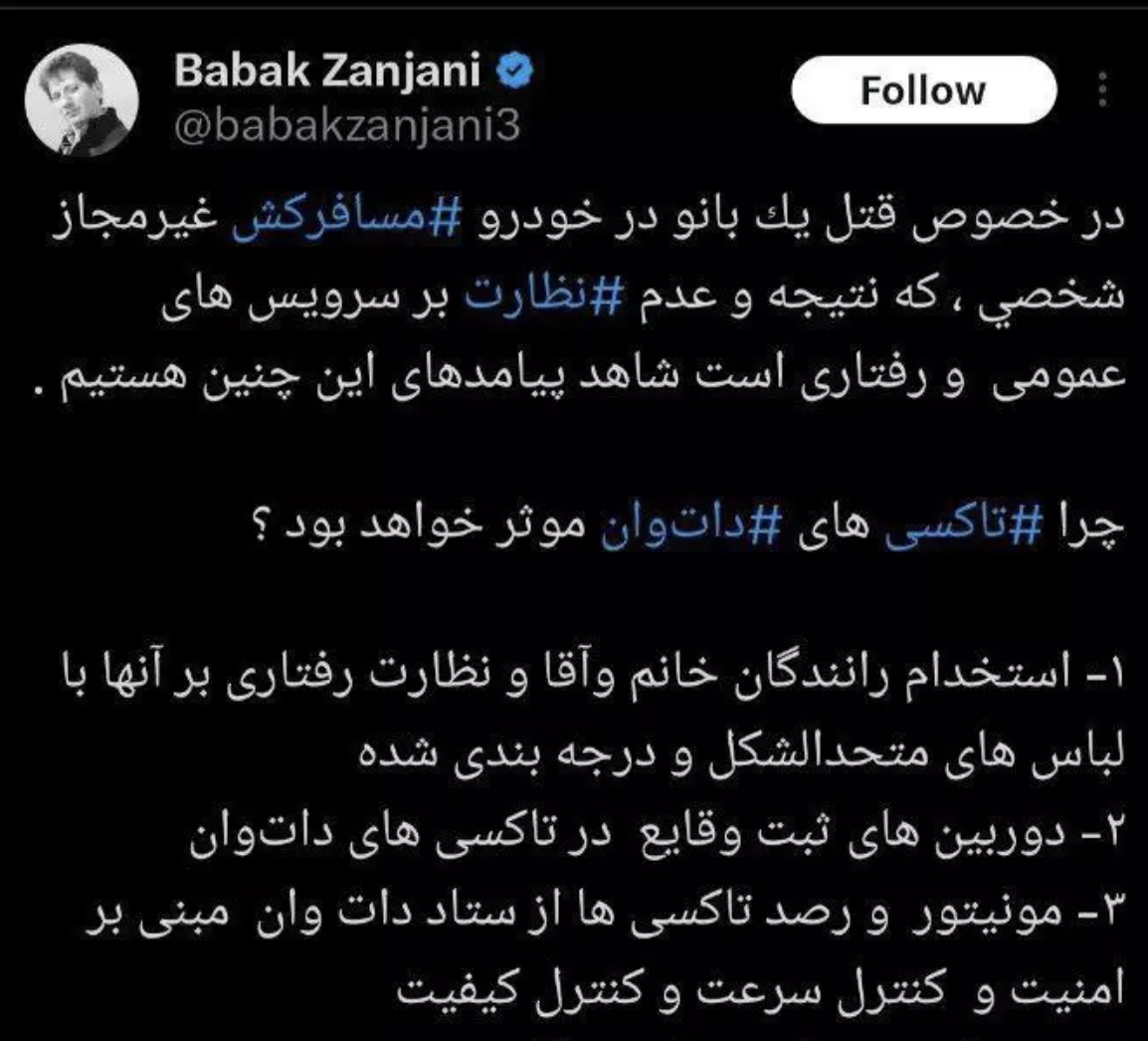

Following this incident, Babak Zanjani published a post on Twitter (X) that explicitly linked this tragedy to the lack of safe and supervised transportation services. This tweet presented "Dot One Taxis" as the essential solution to prevent such tragedies in the future and deemed the company's services necessary for "comfort and security." This marketing tactic was met with a strong public backlash, with many users considering it an unethical exploitation of a human tragedy for commercial advertising. This indicates a deep public distrust of Zanjani's motives.

This marketing strategy reveals a deeper trend of techno-solutionism in response to systemic regulatory failures. The proposed narrative is that technology (surveillance) can solve a problem that is fundamentally related to the government's inability to control unauthorized and unsafe transportation options. The tragic murder occurred in a private, unlicensed vehicle. The systemic problem is the existence of a large, unregulated shadow transportation economy. "One Trip's" marketing, in the face of this regulatory failure, frames the problem as a lack of technology in vehicles. This shifts the burden of safety from the government (enforcement and regulation) to the private sector (surveillance technology) and the individual (choosing the "right" service), which conveniently serves the company's commercial interests.

The Legal Landscape of Privacy in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Article 22 of the Constitution explicitly states that "The honor, life, property, rights, residence, and occupation of individuals are immune from interference." Article 25 of the Constitution protects communications, prohibiting inspection, censorship, recording of conversations, and any form of espionage (eavesdropping) "except by law." But the key question is whether a camera (and supposedly, a microphone) inside OneTrip taxis conflicts with "privacy."

However, there is currently no single codified law in Iran that specifically regulates the installation and use of CCTV cameras. Existing laws address aspects of privacy violations. The Islamic Penal Code criminalizes unauthorized entry into a private residence (Article 694) and eavesdropping/recording of private conversations (derived from Article 25). On the other hand, Article 730 of the Islamic Penal Code (Article 2 of the Cybercrimes Law) criminalizes the unauthorized interception of "content of non-public communications in transit." Article 17 of the Cybercrimes Law also criminalizes the publication of private audio or video without consent if it leads to harm or defamation. The Civil Liability Act (Article 1) stipulates that anyone who harms the "dignity" or "freedom" of another is responsible for compensation, which can be invoked in cases of privacy violations.

Legal interpretations clarify that if eavesdropping occurs in a "non-virtual space," such as installing a sound recording device in a car, and the subject is not "communications in transit in computer or telecommunication systems," it falls outside the scope of the Cybercrimes Law (now part of the Islamic Penal Code). This means the criminalization of eavesdropping in this law does not necessarily cover all instances of recording conversations inside a car cabin. This gap highlights the need for clearer rules regarding surveillance in semi-public spaces.

At the same time, Iran still lacks a comprehensive personal data protection law similar to the GDPR. The "Personal Data Protection Bill" was approved by the government's legal commission in 2024 and sent to the parliament for legal proceedings, but to date, no news of a final law has been published, and the approved text is not publicly available. The absence of a parent law keeps data-driven businesses, from smart taxis to sharing platforms, in regulatory ambiguity and increases the risks of privacy violations.

The SAMAS System: The Line Between State and Private Surveillance

This is the main legal question. The legality of video surveillance depends entirely on this definition. Traditionally, a personal vehicle is considered a private space. However, a key legal interpretation stems from the note to Article 5 of the "Law on the Protection of Promoters of Virtue and Preventers of Vice" (2015). This note states: "Places that are exposed to public view without snooping, such as the common areas of apartments, hotels, hospitals, as well as vehicles, are not considered private." This legal note is the main justification used to argue that the interior of a vehicle is not a private space and is therefore subject to surveillance and enforcement of social codes (like hijab).

However, even if video surveillance is considered permissible, it is not without conditions. There is a strong ethical and quasi-legal expectation that notification must be given. Installing a clear sign with the phrase "This vehicle is equipped with a camera" is considered essential. The purpose of the surveillance must be legitimate (e.g., security), and the data must not be misused. Abusing the footage to harm individuals' reputations could lead to liability under the Cybercrimes Law and the Civil Liability Act. The camera's placement must be public and not intrusively focused on passengers.

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, the line between state and private surveillance is becoming alarmingly blurred. Applications like "One Trip," which provide transportation services, are effectively integrated into the state's surveillance structure. The government uses tools such as facial recognition cameras and the NAZER app to enforce mandatory hijab laws, to the extent that even vehicle license plates are monitored for this purpose. This surveillance trend has extended to ride-hailing services, further threatening passengers' privacy.

In this context, the SAMAS system plays a key role. This system was initially designed to allocate fuel quotas for online taxi drivers, but today it has become a tool for constant monitoring of trips, driver identity, and routes taken. Ride-hailing companies are required to send trip information to Samas in real-time. The lack of legal transparency regarding how this data is used and shared raises fundamental questions about privacy.

At the constitutional level in Iran, Articles 22 and 25 protect human dignity and private communications; but in practice, notes such as the one in the "Law on Promoters of Virtue" nullify these protections in vehicles. This legal contradiction has created an uncertain situation where in-vehicle surveillance has become normalized and even legally justified. This environment not only legitimizes social control by the state but also paves the way for private companies to develop surveillance infrastructures under the guise of "security" or "better service."

The key question is: what are the data-sharing protocols between "One Trip" and security agencies? Can trip information or recorded footage be used solely for violating a social norm like the hijab? This possibility is a serious alarm bell for privacy in Iran, where there is neither an independent regulatory body for data protection nor a clear boundary between state surveillance and corporate activities.

International Experience Regarding the Installation of Cameras in Taxis

Internationally, countries' experiences with the use of cameras and surveillance systems in taxis and public vehicles show significant differences, reflecting the importance each country places on privacy versus the requirements of safety and public security.

In strict models like Australia (Queensland state), the installation of video and audio systems in taxis is mandatory for some services, and the systems must be approved and comply with precise technical specifications. In contrast, countries like Germany and the UK prioritize privacy protection. Germany, by default, opposes permanent recording, and UK laws permit audio recording only in emergency situations (like the activation of a panic button) and with the installation of clear warnings. Any system must comply with strict data protection laws (like GDPR) and undergo a privacy impact assessment.

In the United States and Canada, approaches are state-based and varied. In some states, recording audio without the consent of all parties is illegal. For example, in British Columbia, cameras inside taxis are mandatory, but audio recording is prohibited, and data can only be accessed with a court order. On platforms like Uber and Lyft, users can record audio with end-to-end encryption without the company having access; it is only made available in the event of an official complaint.

In Singapore and Dubai, there are also specific regulations that permit video or even audio recording only in compliance with principles such as notifying the passenger, obtaining a license, having precise storage policies, and preventing the camera from focusing on the passenger's face. In Dubai, the main declared purpose of this surveillance is to monitor driver behavior and improve safety.

Overall, there is a clear global norm: recording audio in public vehicles, except in exceptional cases and with explicit consent, is severely restricted or prohibited. Approaches that involve continuous and uninformed audio recording rarely have legal legitimacy. Transparent regulation and adherence to the principle of data minimization in information collection are the keys to success for countries that have preserved both safety and privacy.

The Return of Babak Zanjani and the "Dot One" Holding

In recent years, the gradual return of Babak Zanjani, an economic criminal on the verge of execution, to Iran's economic scene in the form of the "Dot One" holding company has attracted much attention. This holding company owns the ride-hailing brand "One Trip," one of the ambitious projects whose capital is directly supplied from Zanjani's assets abroad. Although company officials, including Mehdi Ebrahimi, the CEO of Avan Rail Trains, insist that Zanjani is not an official shareholder or director and merely plays the role of a "financial supporter," numerous pieces of evidence indicate his prominent and public presence in promoting the "Dot One" brand on social media.

The "Dot One" brand encompasses a diverse range of services, including air transport (Dot One Air), ride-hailing services (One Trip), financial services (Bit Bank), and logistics activities. This expansion indicates a coordinated effort to rebuild Zanjani's public image and re-enter him into Iran's formal economic structure. The company's legal structure is designed in such a way that it provides access to Zanjani's considerable capital on one hand, while on the other, it protects the company's official image from the notoriety of his history in corruption cases.

Zanjani, who was previously convicted of extensive financial corruption, is now building a new image of himself as a patriotic investor and "economic hero" through social media. The One Trip project and the Dot One holding structure are, in fact, a clever attempt to manage credit risk and gradually return to the formal economy while maintaining a superficial distance from the public face of a convicted criminal.

The Dot One Holding tower and Babak Zanjani's office at the Jahan Kodak intersection, which belonged to Ayandeh Bank, an economic enterprise owned by Ansari, a businessman close to Mojtaba Khamenei, was attacked in the first days of the 12-day war between Israel and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Conclusion

The installation of cameras in Iranian taxis, despite legal ambiguities, may be justifiable if requirements such as public notification and limited data retention are met. However, installing microphones to record audio without explicit consent is clearly illegal under the existing legal framework, as it contradicts Article 25 of the Constitution. A review of available sources on "One Trip" also shows that no credible evidence of the use of a constantly active microphone has been published to date; the claims made only refer to cameras.

From a legal and ethical perspective, international assessments, such as in the UK, Germany, Canada, and Dubai, establish a set of criteria for the legitimacy of in-vehicle surveillance: necessity, proportionality, transparency, minimization, limited retention, technical security, and accountability. Lacking a comprehensive data law, Iran is devoid of these frameworks.

Ultimately, One Trip's attempt to present surveillance as a technological solution to increase security, although ostensibly a response to incidents like the murder of Elaheh Hosseinnejad, could pose a threat to citizens' privacy in the absence of transparency and precise legislation. Until appropriate legislation is enacted, any expansion of audio surveillance must be viewed with caution and skepticism.